How to Raise an Empathetic Child: Tips From a Mother, Grandmother, and Educator

Brain scientists, educators, economists, and public health experts all agree that building a good foundation for healthy relationships begins at birth. The earlier that your child can adapt and develop key social-emotional skills — like attentiveness, persistence, and impulse control — the sooner they can begin engaging in healthy social interactions.

Young children aren’t necessarily born with the skills to engage in healthy relationships, but they ARE born with the potential to develop them.

Parents can teach young children empathy by being the example. Show empathy daily to your children, family, and others in your community. When you show empathy, talk it through with your child and be attentive to their feelings. Use language like: “I know that was hard for you, you seemed sad but you’re safe and loved.” This language will help children become aware of their own emotions and feelings and it will help them become empathetic to others.

A Quick Empathy Checklist for Parents:

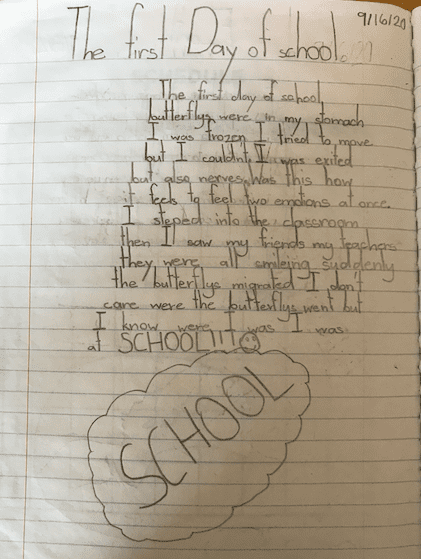

- Explore your child’s emotions together and engage them in imaginative play to learn how to express feelings and better manage their emotions before starting preschool.

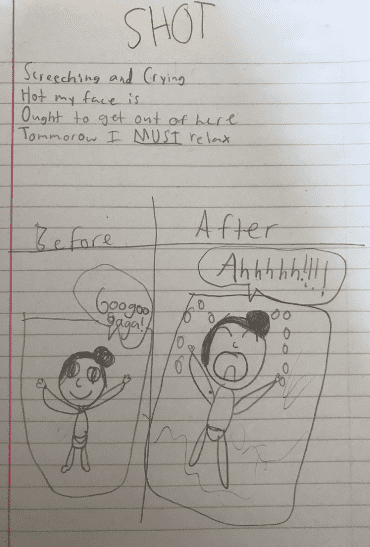

- Teach your child that it’s okay to have whatever feeling they are having — anger, frustration, embarrassment, fear, even rage — but that it is not acceptable for their actions to cross over and affect someone else negatively.

- Teach your child that it’s good to pay attention to others’ feelings and to try to understand why someone else is having negative feelings. There is probably a good reason their friend is feeling angry or afraid.

- Teach your child that it’s never okay for them or anyone else to use their feelings as an excuse to hurt or yell at someone.

Parents play an important role along with teachers in laying a strong foundation for social-emotional skills that will help children form healthy relationships.

Family Activities to Practice Empathy

Here are two fun family activities that you can do at home with your little one to help teach them about empathy:

Make a Kindness Tree

The Kindness Tree is a symbolic way to record kind and helpful actions. Family members place leaves or notes on the tree to represent kind and helpful acts. Parents can notice these acts by saying, “You __(describe the action)__ so __(describe how it impacted others)__. That was helpful/kind!” For example, “Shubert helped Sophie get dressed so we would be on time for our library playdate. That was helpful!”

The Kindness Tree can also grow with families who have children of mixed ages. Initially, young children simply put a leaf on the tree to represent kind and helpful acts. As children grow and learn to write, the ritual evolves to include writing the kind acts down on leaves or sticky notes. Start your own Kindness Tree with this template.

Families with older children can simply use a Kindness Notebook to record kind acts and read them aloud daily or weekly.

Create a "We Care" Center

The We Care Center provides a way for family members to express caring and empathy for others. Fill your We Care Center with supplies like first aid items (Band-Aids, wet wipes, hand sanitizer, scented lotion), card-making supplies (preprinted cards, paper, crayons, sentence starters), and a tiny stuffed animal for cuddling.

When a friend or family member is ill, hurt, or having a hard time, your family can go to the We Care Basket to find a way to show that person you care. At first, parents might need to suggest how and when to use the We Care Center, but your children will quickly understand the intent. The We Care Center encourages the development of empathy by providing a means for children to offer caring and thoughtfulness to others every day.