Parenting With a Big Heart: Big Heart Summer

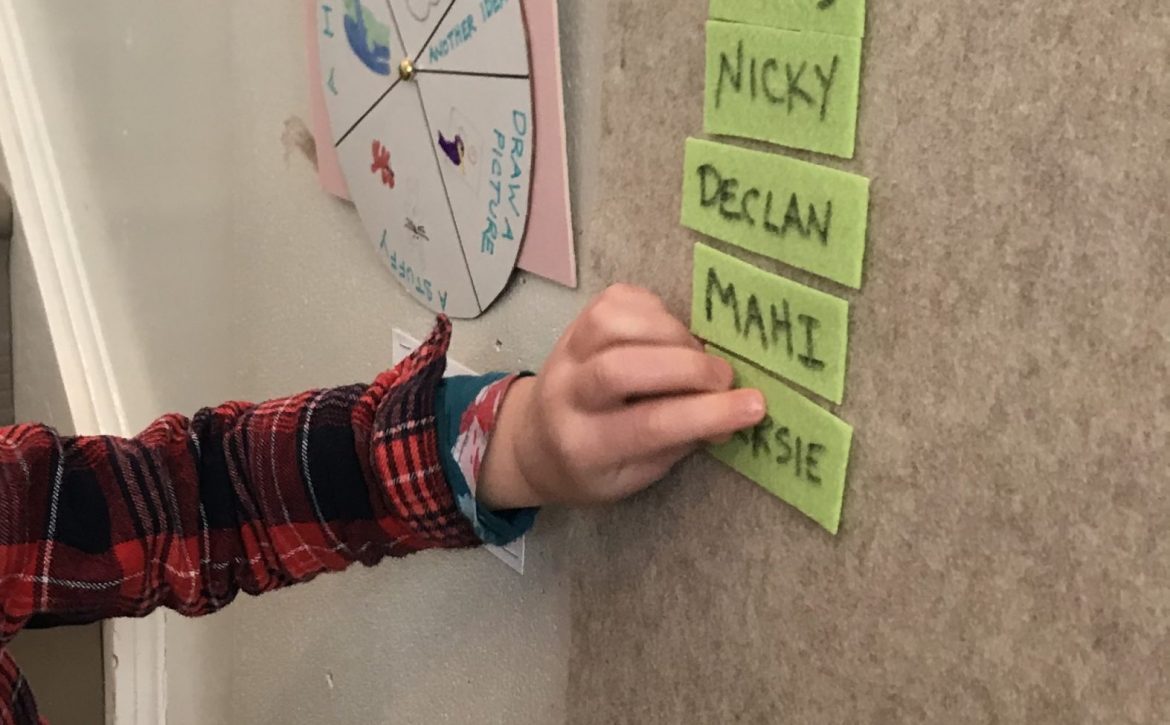

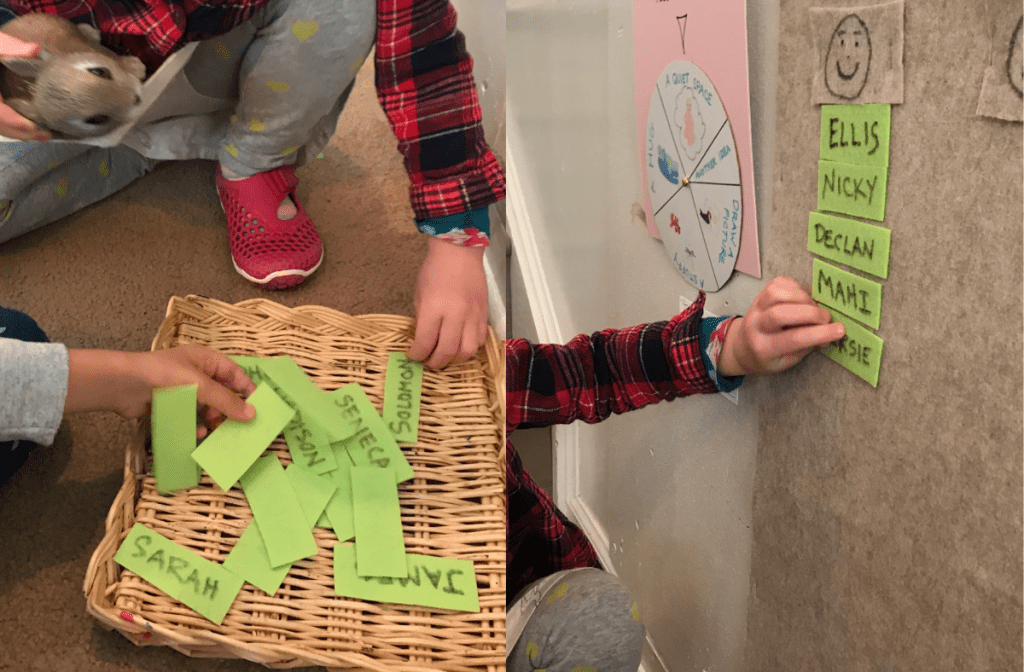

Some families give balloons on the last day of school; in my family, we give binders. Starting a few years ago, on the last day of school, we started a family tradition of giving our kids a binder on the last day of school, full of summer challenges — activities that will motivate them to exercise their brains, hearts, and bodies through the hot summer months.

From the beginning, my kids’ summer challenges included social and emotional challenges — fun activities that grow their hearts. Their heart activities included:

- Write 3 letters to friends or family

- Make 3 new friends

- Do 5 little things and 1 big thing to help other people and the planet

- FaceTime or Zoom with 5 friends who are far away

- Cook & taste foods from 5 different countries

- Write 3 poems or songs expressing your feelings and ideas

Working through a binder full of challenges might not be every kid’s cup of tea — but my kids love paging through their binders and looking for a new adventure, experiment, or project. They love checking things off the list that they’ve accomplished. And as a parent, I love it when they’re learning, trying new things, and growing their whole selves.

What If Summer '22 Was a Big Heart Summer?

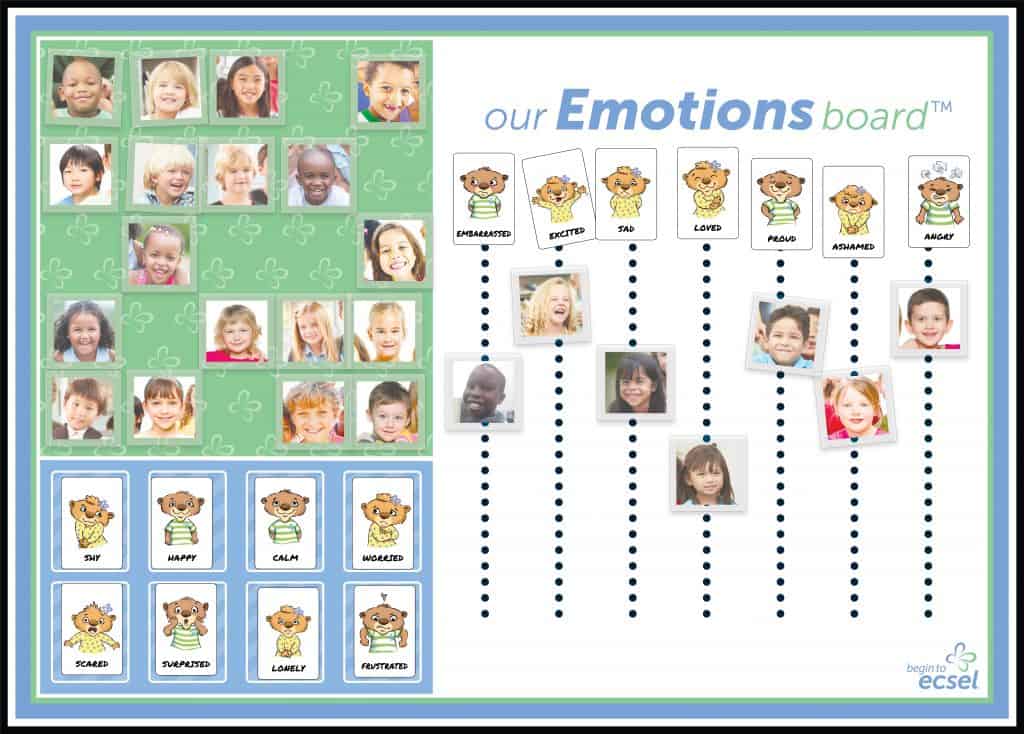

As we jumped into the summer of 2022, I started to wonder: What if we made this a Big Heart Summer for ALL of us and our little ones? Most parents today say that their top concern is making sure children are developing social and emotional skills — understanding themselves and others, being able to manage emotions, interacting with others, making friends, etc. What if our “summer challenges” this year were focused on heart: finding creative ways to grow big hearted kids and practice those all important skills that set us up for success in the world?

This was how Big Heart Summer was born. It’s a creative workbook that families or caregivers can use with children this summer to spark fun, summertime learning, an exploration with our hearts that will help us use this time to understand ourselves and others just a little bit better.

If you want, you can print this out and go through, page by page. More likely, you’ll want to pick the pages that speak to you — or adapt the ideas to your child’s needs and passions. Remember: Big Heart Summer should be fun, creative, and inspiring; it’s not homework!

In my family, this booklet is an instant hit. My youngest already made a postcard for his grandma — we just need to take it to the post office. My oldest is planning out a series of lemonade stands to raise money to help a friend who is sick.

I hope that this can help you to grow YOUR littles’ big hearts this summer. Please share your experiences — or other great ideas you have to inspire families.