Learning Through Holidays

It's the Year of the Tiger!

More than 1 billion people across the world are saying “bye bye” to the Ox and “welcome!” to the Tiger this Lunar New Year, which begins on Feb. 1, 2022.

It’s a time of celebration in parts of Asia and around the world as families gather, eat, and celebrate the new year.

Even if YOUR family doesn’t celebrate Lunar New Year, this is a wonderful time for all families to learn about their own identities and explore the other people and cultures, similarities and differences that surround us.

Teachers and parents can help by:

- Reading stories about the holiday

- Being inspired by art & food

- Noticing similarities and differences

What is Lunar New Year?

“Lunar” means “moon” and the “Lunar New Year” celebrates the beginning of the lunar calendar, which is based on the 12 phases of the moon.

In the same way that many families celebrate the New Year on January 1, the Lunar New Year is an opportunity to look forward and create goals for the coming year.

Each lunar year is represented by one of 12 zodiac animals. Each animal is associated with different traits. For example, this year is “Tiger,” which is known for its bravery and strength. Children born this year are thought to have some of the tiger’s traits!

Families and communities have different ways of celebrating the holiday, including:

- Festivals and parades

- Wearing red, which is considered a good luck color

- Lights and fireworks

- Family gatherings and special meals

Lunar New Year Stories

There are lots of wonderful picture books that you and your child can read to learn about the Lunar New Year. Here are a few great options to get you started:

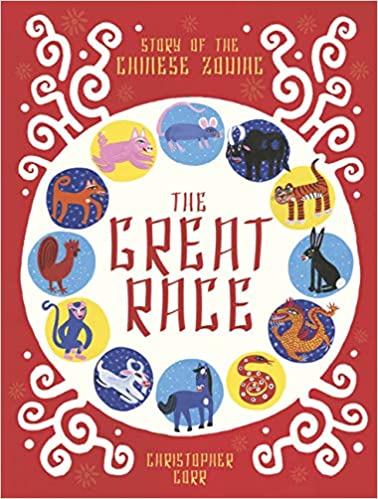

The Great Race: The Story of the Chinese Zodiac

By Christopher Corr

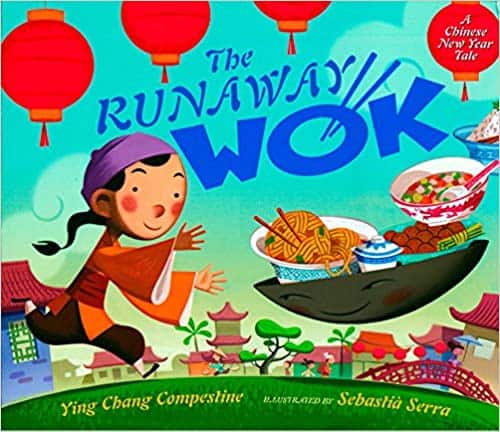

The Runaway Wok: A Chinese New Year Tale

by Ying Chang Compestine and Illustrated by Sebasita Serra

By Adam Wallace and Andy Elkerton

Goldy Luck and the Three Pandas

By Natasha Yim and Illustrated by Grace Zong

Art and Food

The foods that families eat on the Lunar New Year aren’t just food! They represent good luck, prosperity, and togetherness. Here are some examples: Long noodles represent long lives; dumplings and steamed fish stand for wealth and abundance; sticky rice balls stand for togetherness.

The art and decorations of the holiday also hold meaning. For example, many families decorate with lucky colors red and gold.

You can learn more about Lunar New Year by exploring the tastes and colors of the holiday. Be sure to talk to friends and neighbors who celebrate to learn more! Here are some ideas for kid-friendly projects you can try to explore the art and food of the holiday:

- Create a paper lantern with a printable template from our friends at Noggin.

- Create a paper fortune cookie!

- Create (and play) a new year drum.

- Read up on new year food in Bon Appetit Magazine, Food Network, The New York Times, The Woks of Life, or wherever you look for food and cooking inspiration!

Noticing Similarities and Differences

Each of us has an identity — it’s related to who WE are, which is related to our thoughts and beliefs and the traditions of our families and communities. Each of us is different, but we also have a lot in common with other people around the world.

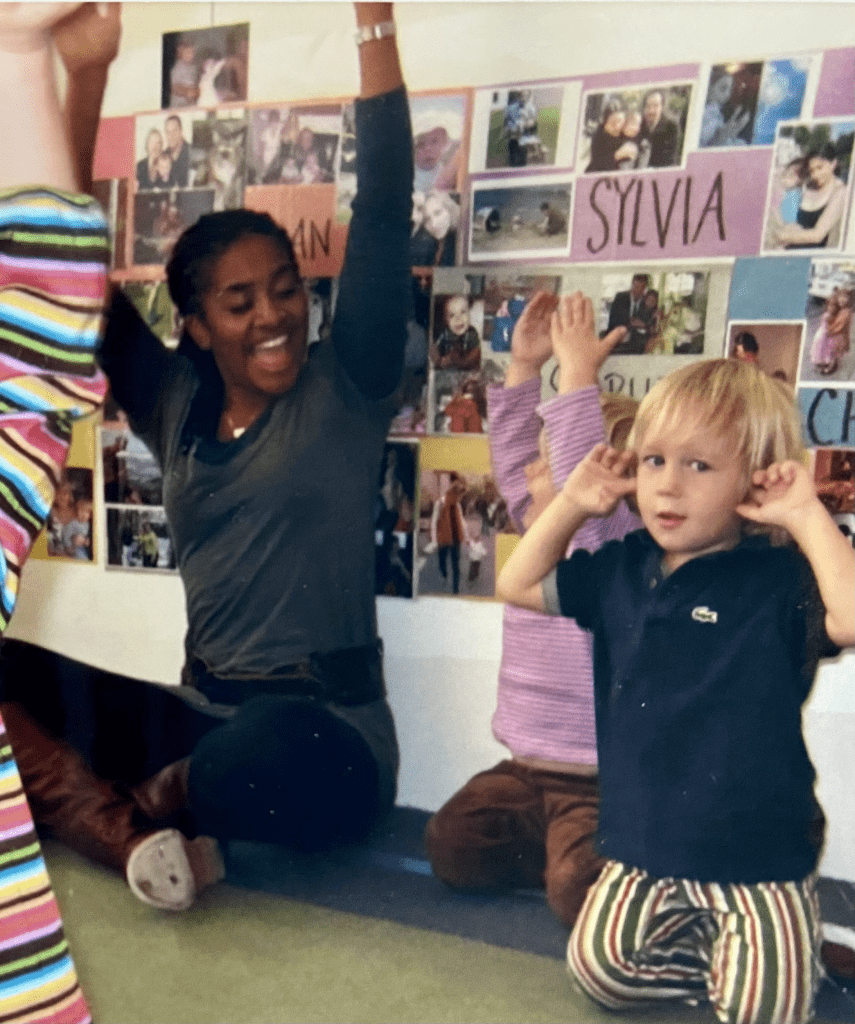

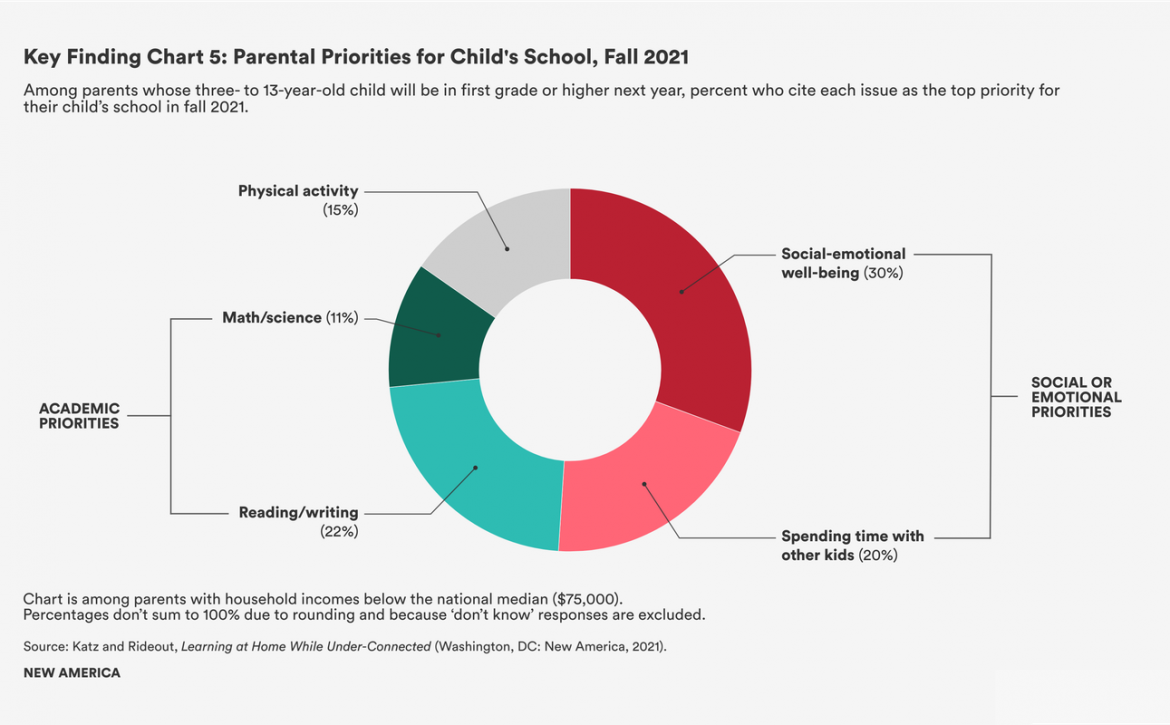

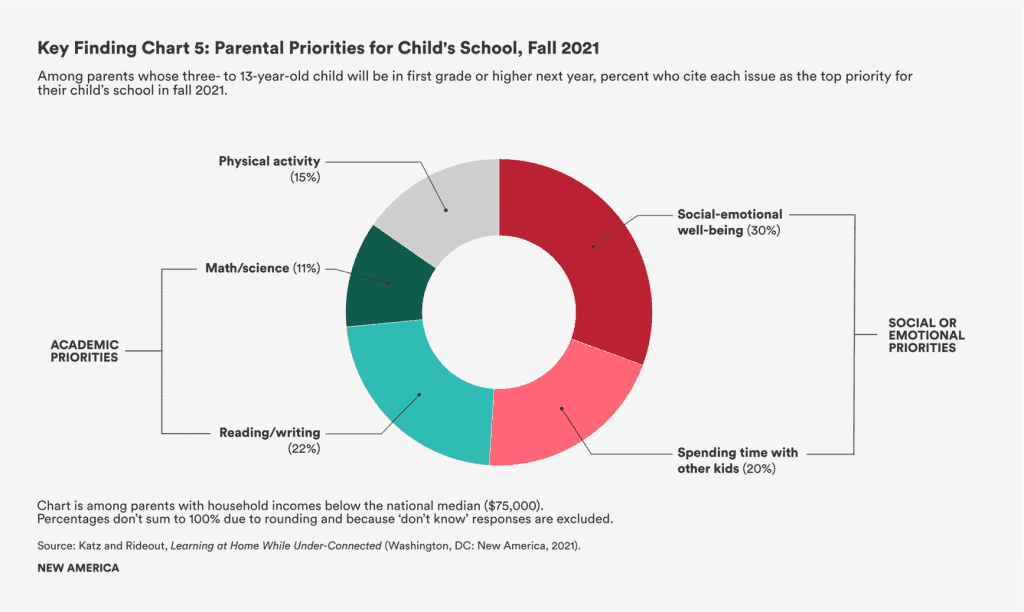

Parents and educators can help prepare children to thrive in our diverse world by helping them learn about their own identities AND by helping them to observe other people and notice the many similarities and differences that surround us.

When various holidays are celebrated around the world, we have an opportunity to think about and explore identity, similarities, and differences with the children in our lives. For the Lunar New Year, try asking:

- How do we celebrate the new year?

- Why do we celebrate the new year?

- What are our wishes for the year ahead?

- What was the animal in the lunar calendar the year YOU were born? (Here’s a page on National Geographic Kids where you can look up your animal.)

- What are some things that are similar and different between the new year’s celebration on January 1 and the Lunar New Year?